Movies vs. TV is not a new debate.

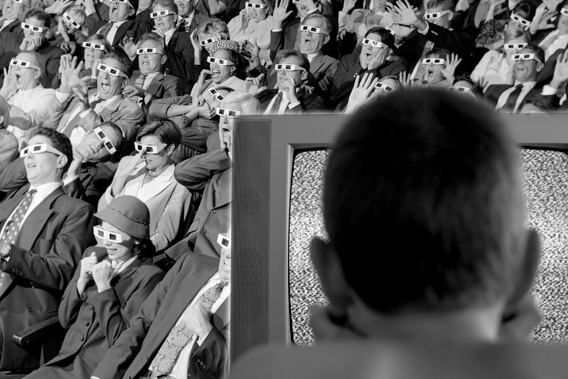

Movies vs. TV is not a new debate. Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker; original photos by Thinkstock.

Who was the first person to say that TV is better than the movies? It?s probably impossible to say, but the argument in its contemporary form may date to October 1995, when Bruce Fretts?with ?additional reporting? from 10 (!) of his colleagues at Entertainment Weekly?offered, over several pages, ?10 simple reasons why the small screen is superior? to the big one. Even if you didn?t read it at the time, the piece will feel strikingly familiar: Replace NYPD Blue and The X-Files with Mad Men and Breaking Bad and the argument made by Fretts is more or less identical in its essentials to the one that over the last six or seven years has appeared in Time, Newsweek, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Vulture, Vanity Fair, Entertainment Weekly (again!), and on blogs too numerous to count.

But that bit of early-EW populist rabble-rousing was pre-Sopranos, when the Emmys were still dominated by the networks. The big awards players at the time were NYPD Blue, ER, and Picket Fences. (Pretty good shows, but come on.) Meanwhile, the movies that year brought us Toy Story, Before Sunrise, Heat, Clueless, Safe, 12 Monkeys, The Usual Suspects, To Die For, Dead Man, Kicking and Screaming, Casino, Seven, Welcome to the Dollhouse?not to mention the five movies nominated for Best Picture, a whole bunch of good films made overseas, and some excellent documentaries. Recently, one writer argued that 1995 was the ?best year ever for movies.? Unlike this year, when the Emmy nominations remind us of the high quality of recent television shows, it was flatly ridiculous to argue for TV?s superiority in 1995.

It would seem, then, that a subset of cultural critics has wanted to make the TV-is-better argument for a long time, well before it was even remotely plausible?and for reasons having little to do with the artistic merits of the best TV shows and the best movies. But why?

On some level, of course, the whole argument is absurd. People will tell you that the dozens of hours TV shows devote to their characters make those characters richer than their cinematic counterparts?but dramatists have known for literally centuries that you only need one night to create a character people will never forget. TV boosters note again and again that, on cable, the writer is king?something I certainly appreciate as a writer. But why is it better for writers, rather than directors, to have final say in what is ultimately a visual medium? And besides, no critic watches enough television and movies to compare the two media with any thoroughness. (One wonders how many of the movies from ?95 listed above that Bruce Fretts, the EW writer, had seen. He keeps bringing up Showgirls.) What?s more, it is becoming harder and harder to keep up: There are so many cable networks and so many movies getting made every year?and the old ?it never played here? excuse no longer works for the littler movies, thanks to video-on-demand and DVDs and so on.

And that, it occurs to me, is precisely the point: The TV-is-better argument is, above all, an attempt to narrow the range of what sophisticated viewers feel obligated to watch. Yes, such polemics sometimes serve other purposes. (Shaming Hollywood studios out of making another board-game-inspired blow-?em-up and turning to taut, Breaking Bad?style thrillers instead, for instance.) But generally the TV-is-better argument is a way of saying, ?I don?t have to keep up with the movies anymore, and neither do you.?

That this is what?s really going on was brought home for me while reading Brett Martin?s very enjoyable new book, Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution, all about TV?s post-Sopranos golden age. In the prologue, Martin writes that the prestige cable drama is ?the signature American art form of the first decade of the 21st century, the equivalent of what the films of Scorsese, Altman, Coppola, and others had been to the 1970s or the novels of Updike, Roth, and Mailer had been to the 1960s.? Put aside, for a second, the overwhelming maleness of that list (though it?s not entirely incidental). Put aside, too, the fact that Norman Mailer wrote his best novels before the 1960s had begun and Roth wrote his well after that decade was over. Focus instead on this idea that there is, at any one point, a single ?signature American art form.? That?s a ridiculous notion. And Martin goes a step further later on in the book: ?Men alternately setting loose and struggling to cage their wildest natures has always been the great American story,? he declares, ?the one you find in whatever happens to be the ascendant medium at the time.? The great American story? You mean there?s only one?

Critics who claim that TV is better than the movies now would generally, it seems, prefer that there only be one. And when it comes to quality, TV remains, for the most part, a great simplifier. Ask nearly any professional critic?not to mention many amateur ones?for the best TV shows of the last decade or so, and you will get a very familiar list, starting with The Sopranos and ending, probably, with Breaking Bad, or maybe, say, Homeland or The Americans. You will almost certainly have heard of every show. You are not likely to encounter the sometimes bewildering variety that a collection of film critics is likely to present you with.

perfect game jon jones vs rashad evans results rashad evans jon jones chuck colson death meteor showers 2012 ufc 145

No comments:

Post a Comment